Fiction

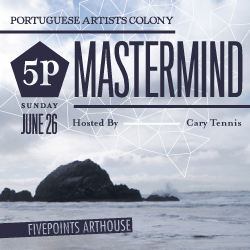

Compassion by Leslie Ingham (as performed at PAC: MasterMind)

Because Mike had money, he had bought the warehouse straight out - no financing. He laid cash in the hands of the previous owners and took it As Is. He could not imagine owing money month after month to some bank. Sounded like purgatory. Sounded like hell.

Ammo World had done a good deal of work on the place, so it turned out to be the most secure craft supply store in California, before Mike even moved in. The walls were thick, doubled concrete blocks. The door was gated. The roof was solid, not like the sheet metal that did for roofs at the auto repair behind and the donut shop beside him. And the whole place was webbed up with cameras.

Most of the square footage was taken up by the store itself, which was divided into departments. There was the Kids’ Zone with Garden Fairy Activity Books, the Wedding Department with white plastic doves covered in bleached chicken feathers, Floral with faux-silk english ivy, and there was Scrap-book Central. In back there were the public toilet, the manager’s office with the west wall shot through with bullet holes, the staff’s toilet and kitchen which was a disturbing and unsavory arrangement curtain or no curtain, and finally, behind the office, the Observation Lounge. Well, that’s what Clive, Ammo World’s retiring owner had called it when he gave Mike the walk through. They stood at a control desk worthy of an evil genius, covered with knobs and sliders. There was one of those chrome and naugahyde egg shaped chairs that was supposed to look futuristic in the ‘70s and a bank of twenty large flat screens showing angled images of empty shelves and corners. “Here you have the Observation Lounge,” Clive had said. “You can see every corner of every part of this building, toilets and hallways and registers. You can see everything that happens. Even had my office hooked up, in case anybody was ever goin’ through my drawers, looking for incrimination of any kind. You have a lawful business, you don’t expect that crap, but there’s a activist under every new employee. You’ll find there is. Anyway, here, here’s the manuals, all down in that drawer, and here,” he pointed at a phone number Sharpied on the wall beside the screens, “here’s the guy who did the work. He can always sort it out. He’s pretty cheap, too, for tech. Or he was for me. Don’t know what he’ll charge you.”

Hiring for the Craft Warehouse was simple. The trick wasn’t finding people smart enough to do it. It was a job for people who could stand to be bored. The trick was finding people who needed the money so badly they wouldn’t trade up as soon as anything better came along. They’d cling. Perhaps most important, they had to be able to interact cheerfully with the steady drift of depressed suburban Moms trying to retain a sense of themselves as human beings by working needlecraft kits, by scrap-booking, by painting single significant words (like Grow or Believe) on rocks while their children crawled through grade school. Vaguely aware that they should have opinions and ideas, the moms would try to chat at the checkout, but they were so far cut off from adult interaction that they no longer remembered what was worth talking about, and so hungry for respect that it mattered how you spoke to them. So it did also require some compassion to work at the Craft Warehouse.

Mike’s store had been open for two years, and he’d almost forgotten about the surveillance system. He’d played with it a bit in the first months, but the few women desperate enough to slip packets of purple dyed feathers into their ridiculous carryalls emblazoned with puppies or unicorns just depressed him. Let them steal the plastic value pack of assorted cotton pompoms retail value $4.99. His working class girls could be on guard for the customer’s middle class misdemeanors. He did not need to watch. But then he hired Thalia, and once Thalia started taking visitors, he couldn’t help but pay attention.

From the beginning he knew Thalia was unlikely to stay. She was too young, too energetic to stand the boredom. Even with no skills she was pretty enough to land a better job. On the other hand, she did show definite signs of compassion. She showed one at her job interview in his office, placing her foot on the chair and bending over to retie her sneaker, taking time with the double bow so he could enjoy the ornate scrolled Asian character tattooed on her sacrum. When she turned to him and sat down, he said, “What does it mean?” and gestured around her at her back. “Oh! That’s the Thai word for Compassion. Only somebody told me it isn’t, but if it isn’t, then the Ink Shop lied to me, so I will have to treat them with compassion, and it ends up meaning compassion anyway,” then, with a lilt and a wide smile, “Can I have the job?” In that minute, listening to the tone of her voice and watching her sway and flirt with the edges of her elastic skirt, short in both directions, he knew he could have her. He could come around the desk to her side and she would lift up her waxy, tangerine lips and shove that skirt a few inches higher, out of the way. Sneakers and all, right on the desk. But he felt, ‘I don’t want to,’ and then he thought of his wife, and remained seated to do the short interview.

She’d never worked anywhere before, or if she had it was such a disaster that she was better off without the reference. But he said yes. That was the point of this business, after all. He wanted a place to give otherwise unemployable women jobs. He wanted a place that didn’t take too much attention. He wanted a place he could bring his little daughter and watch her light up. And he wanted a place that he could imagine his mom walking into, one day.

They left the office and he led her to Mary for orientation. Jeannie, the first one he’d hired and the one surest to remain since for her this job meant food and health insurance for five kids, said, “Aw Mike, now you’ve gone and hired a pretty girl. What’s gonna happen to the rest of us?” Mike said, “Jeannie, I only hire pretty girls. Don’t worry so much,” and she had looked relieved and patted her hair.

He was at the register when the first one arrived on Thalia’s third day. A young man, which was odd enough in the craft supply, but in dark jeans, biker boots and a ponytail, with the knobbed hands of a grease monkey. Thalia appeared out of an aisle to meet him and walked ahead of him past the artificial flowers, not looking back. Mike stood staring a moment ‘til he noticed one of the cameras, and without thinking more walked back to the Observation Lounge.

They were in row 23, a very back corner of the space, where the more expensive picture frames gathered dust from week to week. The rows were irregular, back there, to deal with the oversized easels and mirrors. There wasn’t a straight visual to that aisle on the floor level, but then, there was also nothing you could slip into a pocket. He wondered what had been back there when it was still Ammo World. Gun safes? Roof mounts? Bazookas? Certainly nothing a gun punk could lift. And of course there were security cameras.

The image was surprisingly sharp, now that there was something to see. Thalia had her arms twined around the grease monkey’s neck, pressing herself up to him with a posey-ness she must have learned on the internet, and he was already tugging at his jeans. She spun around and put her hands on her knees, making the oddest, private smile, and Mike barely had time to wonder if he really wanted to watch this, any more than he wanted to watch the shoplifting of the damned, when it was over. The man pressed a few bucks into her hand and she tucked them into her pocket; she smiled her wide, public smile, he shrugged, and it was done.

There were other men, one almost every day, and it didn’t take long for the women at the register to figure it out and have to take a position. Mike watched them moving separately from screen to screen till they drew together in conference at the front. Thalia had disappeared once again down the long aisle with yet another guy who did not fit their marketing demographic. It was a godlike moment for Mike. The rapid fornication appeared, silent and purposive on one screen. Jeannie’s profile, worried, filled another. He could see Mary and Peggy talking, glancing warily down the aisles towards his office and back towards the frame department. Mary, the oldest of them, threw up her hands and walked away, unwilling to get involved. She went back to tagging stock. Jeannie and Alice placed themselves at the endcaps, ready to run interference if he should appear from his office, or a “legitimate” customer wander too far back. He was amazed at their open-heartedness, risking their jobs standing up for a sister. Peggy, young and angry Peggy stayed at the registers, scowling, cleaning all the surfaces. He could see them all, watch them all reacting to what they knew but only he could see. Jeannie stood with her back to the display of mosaic stepping stone kits: “Something Special for Dad.” She and Alice looked excited, and more intense even than the couple in back. As far as he could see they didn’t tell Thalia they were on watch. It was a more pure charity.

As more men came to visit Thalia, Mike perfected his system for following them. He rearranged the camera feeds so he could follow the sequence from the door, past the aisles of plastic beads sorted into banks by color, past the concrete half-wall where the lacquered willow wreaths lay like thin wicker tires. He couldn’t do much with focus but with care he could inconspicuously shift the camera position to point where he could see that odd smile, the one she gave herself when no one was looking. He rearranged the feeds, and banked up the images of the other workers, protectors to the screens on the right, hostiles to the screens on the left. The whole time Thalia was busy Peggy would work with fast, dramatic gestures, as if she were making noise to block out what she knew. Watching them watch out for him made him feel his power. He wasn’t just a manager, an owner. Not just the boss. He was a mastermind.

Plus, he loved to watch her work.

Each time that moment came and she spun around, she would close her eyes and tip her chin high. Before anything happened she had this fascinating, tight little smile. The corners of her mouth compressed into curly eSSes and the point of her lip dipped down. It wasn’t for show - nobody could see it. It was a perfectly private smile to herself.

More than the action, Mike loved to catch that smile.

It usually went pretty smoothly, but then one day she had her caller right when some overdressed housewife, her hair shorn short, was trying to press through the return of three flats of It’s Your Wedding bubble wands. He could see the woman gesturing, her hand on her hip like she owned the place. Even from the camera he could see that the flats had been opened. Some of the wands were half empty. Mary touched them and then wiped her hands. She had tried to refuse the refund, but in the end she buzzed Mike. He had to leave watching to go and rescue his beleaguered checker.

“So it’s not my card. Forget the card. I am telling you, I’ll take a store credit,” she insisted, regardless of Mary’s words.

“But ma’am, you are not the person on the card. You didn’t even buy these. And even if you did, they are not in ‘clean, unused condition’. I just can’t.” Poor Mary. He couldn’t blow the whole thing off, not with Mary trying so hard to keep him in business. But Thalia was walking to the back.

“It’s okay, Mary. Ma’am?” he glanced at the receipt and then turned to the woman, pulling two twenties from his wallet. “Here is your refund. You are banned from the store. Mary, call security.” He was security, but the woman wasn’t to know that.

“You can’t ban me! I will call 911!” Her face was red, even the scalp glowed through her short hair. Mike was walking her towards the door, his arms out to both sides, like a wall forcing her along. He felt oddly conscious that he could give her a big hug with those arms, angry as she was, though the real temptation was to grab on and eject her by force.

“Forever,” he said, and she was left fuming on the step.

He dashed to the back, but it was too late. They were already at it, and there was nothing left to see. Mary was sobbing silently in the wicker basket aisle.

Three days passed during which all the customers were real.

Mike found himself in the Observation Lounge even when there was nothing to see. He’d watch Thalia pace the aisles without even looking at the shelves, hips jutting out sharper with every step. She’d begun pushing her fingers back through her hair to take it off her face, or standing still in Needlework for fifteen minutes at a time checking her phone.

Peggy started bringing her jobs to do. Thalia listened in silence and went back to texting. Peggy scribbled fiercely on her clipboard, keeping track.

On the fourth dry day Mike was at the registers giving Mary her break when a new man walked in. He was tall, maybe bald under the cowboy hat. His shoulders were high and narrow and his low back sagged forward, echoing the cant of his belly. He had a hard pack of cigarettes in his shirt pocket. He passed the registers near the door and wandered a little before Thalia saw him and homed in. Mike saw her head appear and disappear behind the silk flowers as she beelined to intercept him and took him by the hand. She led him back to the frame department, bouncing with excitement. Mike was too agitated to wait for Mary, he beelined himself to the Observation Lounge, and got there, settled into the big egg chair before it seemed much had happened. Thalia and the new man stood, still facing one another, half out of frame on camera 7. The man was looking down away from her face, but his hands were on her shoulders. She tried to rise to her tiptoes to kiss him, but he wouldn’t take the kiss. Held her back? It was hard to tell. Mike had missed something. He fumbled around the control board, looking for another camera he could swing over to get a better view. Thalia’s face had fallen, she looked flat. His unguided fingers switched something and a deep voice echoed softly in the control room, oddly close and intimate,

“No, Darlin’. No, thank you.”

Thalia slipped back down to her flat feet.

“You wasn’t looking for some loving?”

Mike’s ribs ached. She sounded so forlorn. How had he turned the sound on?

“No Ma’am.”

Thalia looked at the hand on her shoulder and saw he was holding a child’s drawing.

“Hey,” the trucker said, “you need the money?”

Thalia’s head swiveled down. She took a step back from him.

“No. No, I’m all right.”

Mike was flicking his eyes back and forth from the screen to the control board, looking for the volume. Why was she so sad? What was she going to do?

The man went on, “My daughter drew this for me with these color change markers. I never seen markers like that before, but she’s real good with them. It has a lot of blue and purple in it.” His voice was soft, looking at Thalia and speaking of his daughter. “I want a little blue frame.”

Thalia didn’t answer, and her face stayed blank. She walked to Jeannie, still standing defiant by the garden mosaic kits: Write your message in this stone. She took Jeannie’s hand and led her back to help the patient trucker, then walked towards the front. Mike’s hands fell from the controls. He was losing her. He couldn’t get to her in time to speak. Peggy was moving towards the registers, out of Scrap-booking, with a cart full of expired stock. She’d be there in just a few seconds. Thalia popped open the drawer of the main register and pulled out all the money, including the bigger bills under the till. She looked up and saw Peggy just turning the corner, and froze. She lifted her face directly to camera 3 and made that little, private smile, eyes bright this time. Mike grabbed the handset and called, “Peggy, Peggy come to the office please.” Thalia turned and walked under the camera, her hand raised to it in farewell. She moved into focus, then out of focus, and was gone.

Ammo World had done a good deal of work on the place, so it turned out to be the most secure craft supply store in California, before Mike even moved in. The walls were thick, doubled concrete blocks. The door was gated. The roof was solid, not like the sheet metal that did for roofs at the auto repair behind and the donut shop beside him. And the whole place was webbed up with cameras.

Most of the square footage was taken up by the store itself, which was divided into departments. There was the Kids’ Zone with Garden Fairy Activity Books, the Wedding Department with white plastic doves covered in bleached chicken feathers, Floral with faux-silk english ivy, and there was Scrap-book Central. In back there were the public toilet, the manager’s office with the west wall shot through with bullet holes, the staff’s toilet and kitchen which was a disturbing and unsavory arrangement curtain or no curtain, and finally, behind the office, the Observation Lounge. Well, that’s what Clive, Ammo World’s retiring owner had called it when he gave Mike the walk through. They stood at a control desk worthy of an evil genius, covered with knobs and sliders. There was one of those chrome and naugahyde egg shaped chairs that was supposed to look futuristic in the ‘70s and a bank of twenty large flat screens showing angled images of empty shelves and corners. “Here you have the Observation Lounge,” Clive had said. “You can see every corner of every part of this building, toilets and hallways and registers. You can see everything that happens. Even had my office hooked up, in case anybody was ever goin’ through my drawers, looking for incrimination of any kind. You have a lawful business, you don’t expect that crap, but there’s a activist under every new employee. You’ll find there is. Anyway, here, here’s the manuals, all down in that drawer, and here,” he pointed at a phone number Sharpied on the wall beside the screens, “here’s the guy who did the work. He can always sort it out. He’s pretty cheap, too, for tech. Or he was for me. Don’t know what he’ll charge you.”

Hiring for the Craft Warehouse was simple. The trick wasn’t finding people smart enough to do it. It was a job for people who could stand to be bored. The trick was finding people who needed the money so badly they wouldn’t trade up as soon as anything better came along. They’d cling. Perhaps most important, they had to be able to interact cheerfully with the steady drift of depressed suburban Moms trying to retain a sense of themselves as human beings by working needlecraft kits, by scrap-booking, by painting single significant words (like Grow or Believe) on rocks while their children crawled through grade school. Vaguely aware that they should have opinions and ideas, the moms would try to chat at the checkout, but they were so far cut off from adult interaction that they no longer remembered what was worth talking about, and so hungry for respect that it mattered how you spoke to them. So it did also require some compassion to work at the Craft Warehouse.

Mike’s store had been open for two years, and he’d almost forgotten about the surveillance system. He’d played with it a bit in the first months, but the few women desperate enough to slip packets of purple dyed feathers into their ridiculous carryalls emblazoned with puppies or unicorns just depressed him. Let them steal the plastic value pack of assorted cotton pompoms retail value $4.99. His working class girls could be on guard for the customer’s middle class misdemeanors. He did not need to watch. But then he hired Thalia, and once Thalia started taking visitors, he couldn’t help but pay attention.

From the beginning he knew Thalia was unlikely to stay. She was too young, too energetic to stand the boredom. Even with no skills she was pretty enough to land a better job. On the other hand, she did show definite signs of compassion. She showed one at her job interview in his office, placing her foot on the chair and bending over to retie her sneaker, taking time with the double bow so he could enjoy the ornate scrolled Asian character tattooed on her sacrum. When she turned to him and sat down, he said, “What does it mean?” and gestured around her at her back. “Oh! That’s the Thai word for Compassion. Only somebody told me it isn’t, but if it isn’t, then the Ink Shop lied to me, so I will have to treat them with compassion, and it ends up meaning compassion anyway,” then, with a lilt and a wide smile, “Can I have the job?” In that minute, listening to the tone of her voice and watching her sway and flirt with the edges of her elastic skirt, short in both directions, he knew he could have her. He could come around the desk to her side and she would lift up her waxy, tangerine lips and shove that skirt a few inches higher, out of the way. Sneakers and all, right on the desk. But he felt, ‘I don’t want to,’ and then he thought of his wife, and remained seated to do the short interview.

She’d never worked anywhere before, or if she had it was such a disaster that she was better off without the reference. But he said yes. That was the point of this business, after all. He wanted a place to give otherwise unemployable women jobs. He wanted a place that didn’t take too much attention. He wanted a place he could bring his little daughter and watch her light up. And he wanted a place that he could imagine his mom walking into, one day.

They left the office and he led her to Mary for orientation. Jeannie, the first one he’d hired and the one surest to remain since for her this job meant food and health insurance for five kids, said, “Aw Mike, now you’ve gone and hired a pretty girl. What’s gonna happen to the rest of us?” Mike said, “Jeannie, I only hire pretty girls. Don’t worry so much,” and she had looked relieved and patted her hair.

He was at the register when the first one arrived on Thalia’s third day. A young man, which was odd enough in the craft supply, but in dark jeans, biker boots and a ponytail, with the knobbed hands of a grease monkey. Thalia appeared out of an aisle to meet him and walked ahead of him past the artificial flowers, not looking back. Mike stood staring a moment ‘til he noticed one of the cameras, and without thinking more walked back to the Observation Lounge.

They were in row 23, a very back corner of the space, where the more expensive picture frames gathered dust from week to week. The rows were irregular, back there, to deal with the oversized easels and mirrors. There wasn’t a straight visual to that aisle on the floor level, but then, there was also nothing you could slip into a pocket. He wondered what had been back there when it was still Ammo World. Gun safes? Roof mounts? Bazookas? Certainly nothing a gun punk could lift. And of course there were security cameras.

The image was surprisingly sharp, now that there was something to see. Thalia had her arms twined around the grease monkey’s neck, pressing herself up to him with a posey-ness she must have learned on the internet, and he was already tugging at his jeans. She spun around and put her hands on her knees, making the oddest, private smile, and Mike barely had time to wonder if he really wanted to watch this, any more than he wanted to watch the shoplifting of the damned, when it was over. The man pressed a few bucks into her hand and she tucked them into her pocket; she smiled her wide, public smile, he shrugged, and it was done.

There were other men, one almost every day, and it didn’t take long for the women at the register to figure it out and have to take a position. Mike watched them moving separately from screen to screen till they drew together in conference at the front. Thalia had disappeared once again down the long aisle with yet another guy who did not fit their marketing demographic. It was a godlike moment for Mike. The rapid fornication appeared, silent and purposive on one screen. Jeannie’s profile, worried, filled another. He could see Mary and Peggy talking, glancing warily down the aisles towards his office and back towards the frame department. Mary, the oldest of them, threw up her hands and walked away, unwilling to get involved. She went back to tagging stock. Jeannie and Alice placed themselves at the endcaps, ready to run interference if he should appear from his office, or a “legitimate” customer wander too far back. He was amazed at their open-heartedness, risking their jobs standing up for a sister. Peggy, young and angry Peggy stayed at the registers, scowling, cleaning all the surfaces. He could see them all, watch them all reacting to what they knew but only he could see. Jeannie stood with her back to the display of mosaic stepping stone kits: “Something Special for Dad.” She and Alice looked excited, and more intense even than the couple in back. As far as he could see they didn’t tell Thalia they were on watch. It was a more pure charity.

As more men came to visit Thalia, Mike perfected his system for following them. He rearranged the camera feeds so he could follow the sequence from the door, past the aisles of plastic beads sorted into banks by color, past the concrete half-wall where the lacquered willow wreaths lay like thin wicker tires. He couldn’t do much with focus but with care he could inconspicuously shift the camera position to point where he could see that odd smile, the one she gave herself when no one was looking. He rearranged the feeds, and banked up the images of the other workers, protectors to the screens on the right, hostiles to the screens on the left. The whole time Thalia was busy Peggy would work with fast, dramatic gestures, as if she were making noise to block out what she knew. Watching them watch out for him made him feel his power. He wasn’t just a manager, an owner. Not just the boss. He was a mastermind.

Plus, he loved to watch her work.

Each time that moment came and she spun around, she would close her eyes and tip her chin high. Before anything happened she had this fascinating, tight little smile. The corners of her mouth compressed into curly eSSes and the point of her lip dipped down. It wasn’t for show - nobody could see it. It was a perfectly private smile to herself.

More than the action, Mike loved to catch that smile.

It usually went pretty smoothly, but then one day she had her caller right when some overdressed housewife, her hair shorn short, was trying to press through the return of three flats of It’s Your Wedding bubble wands. He could see the woman gesturing, her hand on her hip like she owned the place. Even from the camera he could see that the flats had been opened. Some of the wands were half empty. Mary touched them and then wiped her hands. She had tried to refuse the refund, but in the end she buzzed Mike. He had to leave watching to go and rescue his beleaguered checker.

“So it’s not my card. Forget the card. I am telling you, I’ll take a store credit,” she insisted, regardless of Mary’s words.

“But ma’am, you are not the person on the card. You didn’t even buy these. And even if you did, they are not in ‘clean, unused condition’. I just can’t.” Poor Mary. He couldn’t blow the whole thing off, not with Mary trying so hard to keep him in business. But Thalia was walking to the back.

“It’s okay, Mary. Ma’am?” he glanced at the receipt and then turned to the woman, pulling two twenties from his wallet. “Here is your refund. You are banned from the store. Mary, call security.” He was security, but the woman wasn’t to know that.

“You can’t ban me! I will call 911!” Her face was red, even the scalp glowed through her short hair. Mike was walking her towards the door, his arms out to both sides, like a wall forcing her along. He felt oddly conscious that he could give her a big hug with those arms, angry as she was, though the real temptation was to grab on and eject her by force.

“Forever,” he said, and she was left fuming on the step.

He dashed to the back, but it was too late. They were already at it, and there was nothing left to see. Mary was sobbing silently in the wicker basket aisle.

Three days passed during which all the customers were real.

Mike found himself in the Observation Lounge even when there was nothing to see. He’d watch Thalia pace the aisles without even looking at the shelves, hips jutting out sharper with every step. She’d begun pushing her fingers back through her hair to take it off her face, or standing still in Needlework for fifteen minutes at a time checking her phone.

Peggy started bringing her jobs to do. Thalia listened in silence and went back to texting. Peggy scribbled fiercely on her clipboard, keeping track.

On the fourth dry day Mike was at the registers giving Mary her break when a new man walked in. He was tall, maybe bald under the cowboy hat. His shoulders were high and narrow and his low back sagged forward, echoing the cant of his belly. He had a hard pack of cigarettes in his shirt pocket. He passed the registers near the door and wandered a little before Thalia saw him and homed in. Mike saw her head appear and disappear behind the silk flowers as she beelined to intercept him and took him by the hand. She led him back to the frame department, bouncing with excitement. Mike was too agitated to wait for Mary, he beelined himself to the Observation Lounge, and got there, settled into the big egg chair before it seemed much had happened. Thalia and the new man stood, still facing one another, half out of frame on camera 7. The man was looking down away from her face, but his hands were on her shoulders. She tried to rise to her tiptoes to kiss him, but he wouldn’t take the kiss. Held her back? It was hard to tell. Mike had missed something. He fumbled around the control board, looking for another camera he could swing over to get a better view. Thalia’s face had fallen, she looked flat. His unguided fingers switched something and a deep voice echoed softly in the control room, oddly close and intimate,

“No, Darlin’. No, thank you.”

Thalia slipped back down to her flat feet.

“You wasn’t looking for some loving?”

Mike’s ribs ached. She sounded so forlorn. How had he turned the sound on?

“No Ma’am.”

Thalia looked at the hand on her shoulder and saw he was holding a child’s drawing.

“Hey,” the trucker said, “you need the money?”

Thalia’s head swiveled down. She took a step back from him.

“No. No, I’m all right.”

Mike was flicking his eyes back and forth from the screen to the control board, looking for the volume. Why was she so sad? What was she going to do?

The man went on, “My daughter drew this for me with these color change markers. I never seen markers like that before, but she’s real good with them. It has a lot of blue and purple in it.” His voice was soft, looking at Thalia and speaking of his daughter. “I want a little blue frame.”

Thalia didn’t answer, and her face stayed blank. She walked to Jeannie, still standing defiant by the garden mosaic kits: Write your message in this stone. She took Jeannie’s hand and led her back to help the patient trucker, then walked towards the front. Mike’s hands fell from the controls. He was losing her. He couldn’t get to her in time to speak. Peggy was moving towards the registers, out of Scrap-booking, with a cart full of expired stock. She’d be there in just a few seconds. Thalia popped open the drawer of the main register and pulled out all the money, including the bigger bills under the till. She looked up and saw Peggy just turning the corner, and froze. She lifted her face directly to camera 3 and made that little, private smile, eyes bright this time. Mike grabbed the handset and called, “Peggy, Peggy come to the office please.” Thalia turned and walked under the camera, her hand raised to it in farewell. She moved into focus, then out of focus, and was gone.